How to Make Cheese for Pizza at Home in Urdu

History of the food known as pizza

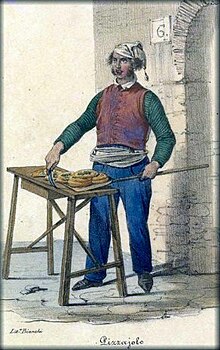

An illustration from 1830 of a pizzaiolo in Naples

The history of pizza begins in antiquity, when various ancient cultures produced basic flatbreads with several toppings.

A precursor of pizza was probably the focaccia, a flatbread known to the Romans as panis focacius, to which toppings were then added.[1] Modern pizza evolved from similar flatbread dishes in Naples, Italy, in the 18th or early 19th century.[2]

The word pizza was first documented in A.D. 997 in Gaeta[3] and successively in different parts of Central and Southern Italy. Pizza was mainly eaten in Italy and by emigrants from there. This changed after World War II when Allied troops stationed in Italy came to enjoy pizza along with other Italian foods.

Origins [edit]

In Sardinia, French and Italian archaeologists have found bread baked over 7,000 years ago. According to Philippe Marinval, the local islanders leavened this bread.[4] Foods similar to pizza have been made since antiquity. Records of people adding other ingredients to bread to make it more flavorful can be found throughout ancient history.

- In the 6th century BC, Persian soldiers serving under Darius the Great baked flatbreads with cheese and dates on top of their battle shields.[5] [6]

- In Ancient Greece, citizens made a flat bread called plakous (πλακοῦς, gen. πλακοῦντος—plakountos)[7] which was flavored with toppings like herbs, onion, cheese and garlic.[8]

- An early reference to a pizza-like food occurs in the Aeneid (ca. 19 BC), when Celaeno, the Harpy queen, foretells that the Trojans would not find peace until they are forced by hunger to eat their tables (Book III). In Book VII, Aeneas and his men are served a meal that includes round cakes (like pita bread) topped with cooked vegetables. When they eat the bread, they realize that these are the "tables" prophesied by Celaeno.[9]

Some commentators have suggested that the origins of modern pizza can be traced to pizzarelle, which were kosher for Passover cookies eaten by Roman Jews after returning from the synagogue on that holiday, though some also trace its origins to other Italian paschal breads.[10] Abba Eban writes "some scholars think [pizza] was first made more than 2,000 years ago when Roman soldiers added cheese and olive oil to matzah".[11] [ better source needed ]

Other examples of flatbreads that survive to this day from the ancient Mediterranean world are focaccia (which may date back as far as the ancient Etruscans); Manakish in Levant, coca (which has sweet and savory varieties) from Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands; the Greek Pita; Lepinja in the Balkans; or Piadina in the Romagna part of Emilia-Romagna in Italy.[12]

Foods similar to flatbreads in other parts of the world include Chinese bing (a wheat flour-based Chinese food with a flattened or disk-like shape); the Indian paratha (in which fat is incorporated); the Central and South Asian naan (leavened) and roti (unleavened); the Sardinian carasau, spianata, guttiau, pistoccu; and Finnish rieska. Also worth noting is that throughout Europe there are many similar pies based on the idea of covering flat pastry with cheese, meat, vegetables and seasoning such as the Alsatian flammkuchen, German zwiebelkuchen, and French quiche.

In 16th-century Naples, a galette flatbread was referred to as a pizza. Known as the dish for poor people, it was sold in the street and was not considered a kitchen recipe for a long time.[13] In 1843, Alexandre Dumas described the diversity of pizza toppings.[14] An often recounted story holds that on June 11, 1889, to honour the queen consort of Italy, Margherita of Savoy, the Neapolitan pizza maker Raffaele Esposito created the "Pizza Margherita", a pizza garnished with tomatoes, mozzarella, and basil, to represent the national colours of Italy as on the Flag of Italy.[15] [16] [17]

Pizza evolved into a type of bread and tomato dish, often served with cheese. However, until the late 19th or early 20th century, the dish was sweet, not savory, and earlier versions which were savory more resembled the flat breads now known as schiacciata.[18] Pellegrino Artusi's classic early-twentieth-century cookbook, La Scienza in cucina e l'Arte di mangiar bene gives three recipes for pizza, all of which are sweet.[19] After the feedback of some readers, Artusi added a typed sheet in the 1911 edition (discovered by food historian Alberto Capatti), bound with the volume, with the recipe of "pizza alla napoletana": mozzarella, tomatoes, anchovies and mushrooms.[20]

However, by 1927, Ada Boni's first edition of il talismano della felicità (a well-known Italian cookbook) includes a recipe using tomatoes and mozzarella.[21]

Innovation [edit]

The innovation that led to flatbread pizza was the use of tomato as a topping. For some time after the tomato was brought to Europe from the Americas in the 16th century, it was believed by many Europeans to be poisonous, like some other fruits of the Solanaceae (nightshade) family are. However, by the late 18th century, it was common for the poor of the area around Naples to add tomato to their yeast-based flatbread, and so the pizza began.[ citation needed ] [22] The dish gained popularity, and soon pizza became a tourist attraction as visitors to Naples ventured into the poorer areas of the city to try the local specialty.

According to documents discovered by historian Antonio Mattozzi in State Archive of Naples, in 1807 already 54 pizzerias existed, with their owners and addresses.[23] In the second half of the nineteenth century they increased to 120.[24]

In Naples, two others figures connected to the trade existed — the pizza hawker (pizzaiuolo ambulante), who sold pizza, but did not make it, and the seller of pizza "a oggi a otto", who made pizzas, but sold them in return for a payment for seven days.[25]

The pizza marinara method has a topping of tomato, oregano, garlic, and extra virgin olive oil. It is named "marinara" because it was traditionally the food prepared by "la marinara", the seaman's wife, for her seafaring husband when he returned from fishing trips in the Bay of Naples.

The margherita is topped with modest amounts of tomato sauce, mozzarella, and fresh basil. It is widely attributed to baker Raffaele Esposito, who worked at the restaurant "Pietro... e basta così" ("Pietro... and that's enough"), established in 1880 and still in business as "Pizzeria Brandi". Though recent research casts doubt on this legend,[26] the tale holds that, in 1889, he baked three different pizzas for the visit of King Umberto I and Queen Margherita of Savoy. The Queen's favorite was a pizza evoking the colors of the Italian flag — green (basil leaves), white (mozzarella), and red (tomatoes).[27] According to the tale, this combination was named Pizza Margherita in her honor. Although those were the most preferred, today there are many variations of pizzas.

"Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana"[28] ("True Neapolitan Pizza Association"), which was founded in 1984, has set the very specific rules that must be followed for an authentic Neapolitan pizza. These include that the pizza must be baked in a wood-fired, domed oven; that the base must be hand-kneaded and must not be rolled with a pin or prepared by any mechanical means (i pizzaioli — the pizza makers — make the pizza by rolling it with their fingers) and that the pizza must not exceed 35 centimetres in diameter or be more than one-third of a centimetre thick at the centre. The association also selects pizzerias all around the world to produce and spread the verace pizza napoletana philosophy and method.

There are many famous pizzerias in Naples where these traditional pizzas can be found such as Da Michele, Port'Alba, Brandi, Di Matteo, Sorbillo, Trianon, and Umberto. Most of them are in the ancient historical center of Naples. These pizzerias follow even stricter standards than the specified rules by, for example, using only San Marzano tomatoes grown on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius and drizzling the olive oil and adding tomato topping in only a clockwise direction.

The pizza bases in Naples are soft and pliable. In Rome, they prefer a thin and crispy base. Another popular form of pizza in Italy is "pizza al taglio", which is pizza baked in rectangular trays with a wide variety of toppings and sold by weight.

In 1962, the "Hawaiian" pizza, a pizza topped with pineapple and ham, was invented in Canada by restaurateur Sam Panopoulos at the Satellite Restaurant in Chatham, Ontario.[29]

In December 2009, the pizza napoletana was granted Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status by the European Union.[30]

In 2012, the world's largest pizza was made in Rome and it was measured to be 1261.65 square meters in area.[31]

In 2016, robotics company BeeHex, widely covered in the media, was building robots that 3D-printed pizza.[32]

In December 2017, the pizza napoletana was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[33]

Pizza in Canada [edit]

Canada's first pizzeria opened in 1948, Pizzeria Napoletana in Montreal.[34] Starting in the late 1950s, the first pizza ovens started entering the country.[35] It gained popularity throughout the 1960s, with many pizzerias and restaurants opening across the country. Pizza was mostly served in restaurants and small pizzerias. Most pizza restaurants across Canada also serve popular Italian cuisine in addition to pizza, such as pasta, salad, soups and sandwiches. Fast-food pizza chains also provide other side options for customers to choose from, in addition to ordering pizza, including chicken wings, fries and poutine, salad, and calzones. Pizza Pops are a Canadian calzone-type snack introduced in the 1960s. Pizza chains across Canada can be found in shopping centres, schools, and neighbourhood plazas, with the majority of these chains offering a sit-and-dine facility for customers.

The most distinct pizza in Canada is the "Canadian" pizza. A "Canadian" pizza is usually prepared with tomato sauce, mozzarella cheese, pepperoni, mushrooms, and bacon. Many variations of this pizza exist, but the two standout ingredients that make this pizza distinctly Canadian are bacon and mushrooms. Pizzas in Canada are almost never served with "Canadian bacon", or back bacon as it's referred to in Canada. Rather, side bacon is the standard pork topping on pizza.

In the province of Quebec Pizza-ghetti is a combination meal commonly found in fast food or family restaurants. It consists of a pizza, sliced in half, accompanied by a small portion of spaghetti with a tomato based sauce. Although both pizza and spaghetti are considered staples of Italian cuisine, combining them in one dish is completely unknown in Italy. A popular variant involves using spaghetti as a pizza topping, under the pizza's mozzarella cheese

Some of Canada's successful pizza brands include: Boston Pizza, Pizza Pizza, and Vanelli's. Boston Pizza, also known as BP's in Canada, and "Boston's—the Gourmet Pizza" in the United States and Mexico, is one of Canada's largest franchising restaurants.[36] The brand has opened over 325 locations across Canada and 50 locations in Mexico and the US.[36] The first Boston Pizza location was opened in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1964, and operated under the name "Boston Pizza & Spaghetti House", with locations still opening across the nation.

Pizza Pizza, and its subsidiary chain Pizza 73 in Western Canada, are among Canada's largest domestic brands based in Ontario.[ citation needed ] To date, they have over 500 locations nationwide, and fill more than 29 million orders annually.[37]

Vanelli's is an international pizza chain that is based in Mississauga.[38] The chain first opened in 1981, serving both pizza and other fresh Italian cuisine, such as pasta and Italian sandwiches.[38] In 1995, the brand opened its first international location in Bahrain and became an international success. The brand continued to open additional locations across the Middle East, with chains now opened in the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, and Morocco.[39] There are over 110 locations worldwide; making Vanelli's the first pizza brand in Canada to open locations internationally.

With pizza gaining popularity across the nation, major American pizza chains such as Pizza Hut, Domino's Pizza and Little Caesars have expanded their locations in Canada, competing against the domestic Canadian brands. The major American pizza chains have brought their signature classic pizza recipes and toppings into their Canadian chains, offering their traditional classic pizzas to Canadian customers. However, the American chains have also created Canadian specialty pizzas that are available only in Canada.

Pizza in the United States [edit]

A pizza pie. In the background is a calzone

Pizza first made its appearance in the United States with the arrival of Italian immigrants in the late 19th century[40] and was popular among large Italian populations in New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Trenton and St. Louis.[ citation needed ]

According to a 2009 response published in a column on Serious Eats, the first printed reference to "pizza" served in the US is a 1904 article in The Boston Journal.[41] Giovanni and Gennaro Bruno came to America from Naples, Italy, in 1903 and introduced the Neapolitan pizza to Boston. Later, Vincent Bruno (Giovanni's son) went on to open the first pizzeria in Chicago.[42]

Conflicting stories have the first pizzeria opening in 1905 when Gennaro Lombardi applied for a license in New York to make and sell pizza. One of the generally accepted first US businesses to sell pizza, Lombardi's, opened in 1897 as a grocery store at 53½ Spring Street, with tomato pies wrapped in paper and tied with a string at lunchtime to workers from the area's factories. In 1905, putative founder Gennaro Lombardi received a business license to operate a pizzeria restaurant, and soon had a clientele that included Italian tenor Enrico Caruso. He later passed the business on to his son, George.[43]

Pizza was brought to the Trenton area of New Jersey with Joe's Tomato Pies opening in 1910, followed soon by Papa's Tomato Pies in 1912. In 1936, De Lorenzo's Tomato Pies was opened. While Joe's Tomato Pies has closed, both Papa's and Delorenzo's have been run by the same families since their openings and remain among the most popular pizzas in the area. Frank Pepe Pizzeria Napoletana in New Haven, Connecticut, was another early pizzeria which opened in 1925 (after the owner served pies from local carts and bakeries for 20–25 years) and is famous for its New Haven–style Clam Pie. Frank Pepe's nephew Sal Consiglio opened a competing store, Sally's Apizza, on the other end of the block, in 1938. Both establishments are still run by descendants of the original family. When Sal died, over 2,000 people attended his wake, and The New York Times ran a half-page memoriam. The D'Amore family introduced pizza to Los Angeles in 1939.

Before the 1940s, pizza consumption was limited mostly to Italian immigrants and their descendants. Following World War II, veterans returning from the Italian Campaign, who were introduced to Italy's native cuisine proved a ready market for pizza in particular,[44] touted by "veterans ranging from the lowliest private to Dwight D. Eisenhower".[45] By the 1960s, it was popular enough to be featured in an episode of Popeye the Sailor.[46] Pizza consumption has exploded in the U.S with the introduction of pizza chains such as Domino's, Pizza Hut, and Papa John's.[47] [ failed verification ]

Two entrepreneurs, Ike Sewell and Ric Riccardo, invented Chicago-style deep-dish pizza, in 1943. They opened their own restaurant on the corner of Wabash and Ohio, Pizzeria Uno.[48]

Pizza chains sprang up with pizza's popularity rising. Leading early pizza chains were Shakey's Pizza, founded in 1954 in Sacramento, California; Pizza Hut, founded in 1958 in Wichita, Kansas; and Little Caesars, founded in 1959 in Garden City, Michigan.[ citation needed ] Later restaurant chains in the dine-in pizza market were Bertucci's, Happy Joe's, Monical's Pizza, California Pizza Kitchen, Godfather's Pizza, and Round Table Pizza,[49] as well as Domino's, Pizza Hut, Little Caesars and Papa John's. Pizzas from take and bake pizzerias, and chilled or frozen pizzas from supermarkets make pizza readily available nationwide. 13% of the US population consumes pizza on any given day.[50]

See also [edit]

- Food history

- Pizza in China

References [edit]

- ^ Anderson, Burtan (1994). Treasures of the Italian Table . William Morrow and Company. p. 318. ISBN978-0688115579.

- ^ Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History . London: Reaktion. pp. 21–22. ISBN978-1-86189-391-8.

- ^ Salvatore Riciniello (1987) Codice Diplomatico Gaetano, Vol. I, La Poligrafica

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2009. CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Pizza, A Slice of American History" Liz Barrett (2014), p.13

- ^ "The Science of Bakery Products" W. P. Edwards (2007), p.199

- ^ Plakous, Liddell and Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon", at Perseus

- ^ Crompton, Dan (2016). A Classical Primer: Ancient Knowledge for Modern Minds. Michael O'Mara. ISBN978-1782435112.

- ^ "Aeneas and Trojans fulfill Anchises' prophecy". Archived from the original on March 29, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ Nissan, Ephraim; Alinei, Mario (2013). "The Pizza and the Pitta: The Thing and Its Names, Antecedents and Relatives, Ushering Into Globalization". In Felecan, Oliviu; Bughesiu, Alina (eds.). Onomastics in Contemporary Public Space. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN978-1443852173.

- ^ Bamberger, David; Eban, Abba Solomon (1979). My People: Abba Eban's History of the Jews, Volume 2. Behrman House. p. 228. ISBN0874412803.

- ^ "Food and Drink – Pide – HiTiT Turkey guide". Hitit.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ "History of Pizza Margherita". tobetravelagent.com. April 9, 2012. Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ Dumas, Alexandre (1843). Le Corricolo (in Corsican) (Oeuvres Complètes (1851) ed.). p. 91. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ Danford, Natalie (October 1994). "Beyond Pizza". Vegetarian Times. Active Interest Media (109). ISSN 0164-8497.

- ^ "Rallying to protect 'real' pizza". Philadelphia Inquirer. April 5, 1989.

- ^ "Pizza purists out to protect patriotic pie". Lakeland Ledger. Associated Press. March 2, 1989.

- ^ Alexandra Grigorieva, "Naming Authenticity and Regional Italian Cuisine [1]," in Richard Hosking, ed., Authenticity in the Kitchen: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2005 (Prospect Books, 2006): 211–216.

- ^ Pellegrino Artusi, La scienza in cucina e l'Arte di mangiar bene (1911; rpr. Torino: Einaudi, 2001)

- ^ Mattozzi, Antonio e Donatella (2016) "Pizze, pizzerie e pizzaiuoli a Napoli tra Sette e Ottocento" p.35, in Pizza. Una grande tradizione italiana. Bra: Slow Food Publisher

- ^ Grigorieva. Naming Authenticity. pp. 211–212.

- ^ Turim, Gayle. "Who Invented Pizza?". History. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ Mattozzi, Antonio (2015) Inventing the Pizzeria: a History of Pizza Making in Naples, Bloomsbury Academic, pp.16–17

- ^ Mattozzi, Antonio Inventing the Pizzeria, Distribution Maps, p.xxxiv

- ^ Mattozzi, Antonio Inventing the Pizzeria, p.28

- ^ "Was margherita pizza really named after Italy's queen?". BBC Food. December 28, 2012. Archived from the original on December 31, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ "American Pie". American Heritage. April–May 2006. Archived from the original on July 12, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

Cheese, the crowning ingredient, was not added until 1889, when the Royal Palace commissioned the Neapolitan pizzaiolo, Raffaele Esposito, to create a pizza in honor of the visiting Queen Margherita. Of the three contenders he created, the Queen strongly preferred a pie swathed in the colors of the Italian flag — red (tomato), green (basil), and white (mozzarella).

- ^ "Avpn – Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana". Pizzanapoletana.org. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ Nosowitz, Dan (November 4, 2015). "Meet the 81-Year-Old Greek-Canadian Inventor of the Hawaiian Pizza". Atlas Obscura. Unknown. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ^ Hooper, John (December 9, 2009). "Pizza napoletana awarded special status by EU". The Guardian. London. Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- ^ "Largest pizza". Guinness World Records . Retrieved January 13, 2017. From the given area, the circular pizza had a diameter of approximately 40.08 m, or 131.5 ft.

- ^ "NASA wants astronauts to have 3D printed pizza, and this startup is building a printer to make it happen". Digital Trends. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ "Naples' pizza twirling wins Unesco 'intangible' status". The Guardian. London. December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "From the archives: Montreal pizzerias, the labour of doughy love". montrealgazzette.com. April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Bringing the first pizza ovens to Canada in the 1950s". Canada.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ a b "Boston Pizza Company History" (PDF). bostonpizza.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ "Hungry? Want Pizza? There's an app to help you order one". techvibes.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ a b "About Us". vanellisrestaurant.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ "locations". vanellisrestaurant.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History . Reaktion Books. p. 48. ISBN978-1-86189-630-8.

- ^ Kuban, Adam (January 5, 2009). "Dear Slice: Boston May Have Had the First Pizza in America". Dear Slice (blog). Serious Eats. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ Bernier, Brian (October 29, 2014). "Readers weigh in on top Sheboygan, Manitowoc pizzerias". The Sheboygan Press.

- ^ Nevius, Michelle; Nevius, James (2009). Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City. New York: Free Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN978-1416589976.

- ^ Turim, Gayle. "A Slice of History: Pizza Through the Ages". History.com. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ Miller, Hanna (2006). "American Pie". American Heritage Foundation. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "Popeye's Pizza Palace". The Big Cartoon Database.

- ^ "Pizza Garden: Italy, the Home of Pizza". CUIP Chicago Public Schools – University of Chicago Internet Project. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ Higgins, Dennis. (2014). Tomorrow's borrowed trouble. Whiskey Creek Press. ISBN9781633556850. OCLC 953831802.

- ^ "CBC Archives: New 50s Food – Pizza! 1957". YouTube. September 17, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Rhodes, Donna G.; Adler, Meghan E.; Clemens, John C.; LaComb, Randy P.; Moshfegh, Alanna J. (February 2014). Consumption of Pizza (PDF). Dietary Data Brief (Report). 11. Food Surveys Research Group, USDA. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

Further reading [edit]

- Barrett, Liz (2014). Pizza: A Slice of American History. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press

- Dickie, John (2010). Delizia: The Epic History of the Italians and Their Food. New York: Free Press.

- Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History. London: Berg.

- Mattozzi, Antonio (2015). Inventing the Pizzeria: A History of Pizza Making in Naples. London: Bloomsbury Academic

How to Make Cheese for Pizza at Home in Urdu

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_pizza